Your breasts/ sliced off

coming home to the body I left behind, part 1. (After explant surgery, and long before)

There are moments that break the trance of logic and reason, and send the psyche hurdling into the mystery. Some people call them coincidences, perhaps to safeguard against falling into that unexplainable sense that something bigger really is going on here.

I personally love that feeling, so I call those moments synchronicities. The risk of granting meaning to them is that sometimes, they carry an ominous energy and leave an unsettling aftertaste. Synchronicities can offer hope, and they can haunt, too.

If you want to take the good kind for its encouragement, then it has to come with the troublesome kind and its residue of fear; those little moments that leave a shudder and the mind, disturbed, echoing, “What does that mean?”

It is in times like those where some familiarity with symbol, metaphor and dreamwork can help to soften the dread that comes with taking magic too literally. In this way, poetry - by nature - helps me to remember never to take words at face value.

Thankfully, I do have a healthy inner skeptic to balance my magical thinking (and serve as a buzzkill to my inner meaning-maker). Still, I tend to generally be somewhat superstitious. I can’t help but make meaning from the patterns I encounter, and sometimes they haunt me.

I had one of those haunting synchronicities in the middle of 2024. As I type now, in January of 2026, the fact that that this happened about 1.5 years ago now is absolutely mind-boggling to me. Time seems warped in this decade, and it truly feels like just months ago.

I was still healing (slowly, to my great frustration) from breast explant surgery.

I had my implants (large profile, saline) drained and then removed after 17.5 years of living as a person who wore size small clothing with a DD bra size. It was bound to be a shock to go back to the breasts I could barely remember since I had them enhanced at age 23.

But I had also been excited for it, hoping I would reclaim a lot of life force and vitality that my body seemed to be starved of lately. What I did not expect was the depth of ongoing multi-dimensional inner work and external support that my healing journey would demand of me from that point on. It would be years-worth, in fact, although I did not know it at the time.

At that point, mid-2024, I was focused mostly on the physical: rehabilitating my tense chest, neck and shoulder muscles that had gotten stiff from immobility, stress and nerve interference.

I had a strange mixture of more pain and more numbness; a louder body preoccupying my attention that I felt more disconnected from than ever before.

My chest was jarring to see when I was undressed.

The expanded skin, which now appeared empty after so many years in the inflated shape, did not bounce back to fit my memory of those natural breasts I had altered. I had a ‘capsulectomy’ as well (removal of the capsule the body forms around the foreign object), and that cost me a bit more tissue, but was supposed to be the most effective for removing potential pathogens and bacteria, if my implants had developed any. Neither I or the doctor could know until they got in and removed them for testing.

I would learn after surgery that mine were clear: no bacterial infection, no clear signs of direct problems. But, in the mysterious world of breast implant illness, there is a proposed theory that in the right conditions of systemic overload, the body can start to reject an otherwise healthy implant that has been there peacefully for a long time. This autoimmune-like behavior usually comes with chronic inflammation. It just begins to go to battle with what was previously benign.

So, I was relieved that in this way it seemed I was one of the luckier ones whose implant capsules were not an obvious breeding ground for toxicity or acute infection. But it left my the root source of my chronic health issues, insomnia, fatigue and joint pain an unsolved mystery.

I maintained hope that offloading my body of the presence of my implants would ultimately support my immune system and be a little less internal battle to hold. (Never mind the absolute assault I had just introduced with major surgery, anesthesia, and the pandora’s box of sleeping dragons that the intrusion opened in my nervous system).

As I was healing, my bloated belly was draining fluid from surgery and it protruded farther than my breasts did for the first time in my life. It was a shocking reunion with the lower half of my body, which was now so visible across the flatlands of my chest wall.

I prayed every day that a morning would come where the way they looked would begin to visibly improve; where my breasts, now all but gone, would start to grow back. “Fluffing” out, it was called, according to my internet research. In the meantime, I focused on other elements of my healing journey.

At that time, I was still focused on finding the right healing team (outside of me) that could help. I had a chiropractor who helped with scar massage. I got lymphatic work. I spoke to a few different counselors. I went to PT occasionally.

A part of that process included occasional bodywork sessions from a gifted hands-on healer a friend had referred me to, who would - with permission - often share what she saw in her inner vision after she worked on a client’s body.

So here we are, back in that moment of synchronicity—

I had just emerged from a bodywork session with her in my home. She shared at the end, that she saw a vision of me having my breasts cut off in a past lifetime (those were her exact words), among numerous other violent deaths in other lives. Evidently, violent suffering was kind of my karmic thing, according to her inner dreamscape.

Now, I am not whole-heartedly convinced in the past-life cosmovision. Nor was I particularly convinced of this transmission. The suggestion that my breasts had been chopped off in another lifetime and I was somehow reliving this experience seemed too on-the-nose to be true. So my inner skeptic was right there at the front lines of my mind, politely filtering her reflection through discerning dismissiveness. But I did feel a surprising chill of resonance, because of my own dreams and visions. I held it all very lightly. “Wow, Interesting!” I said, before thanking her and bidding her farewell with a hug.

The very next thing that I did was go to the bathroom.

I remember it rather vividly for how long ago and ordinary the experience was. I did not turn on the light. I left the door open, so the natural sunlight spilled in. I was working on my own poetry book that year, and had been swimming in other poets’ books to get a feel for them as tangible artifacts (the layout, the paper, the weight, etc), while I channeled the design and feel of my own.

So there, on a shelf in front of the toilet, I had left Adrienne Rich’s The Dream of a Common Language, which I had only recently found after a cover illustrator said my work somewhat reminded me of hers (massive flattery, it turned out). I was finally getting to know Adrienne Rich as a poet then, and I was smitten.

On an impulse, I did what I often do with poetry books and I superstitiously flipped the book like a deck of oracle cards to a random page, asking my soul for a guiding message as I always seem to be.

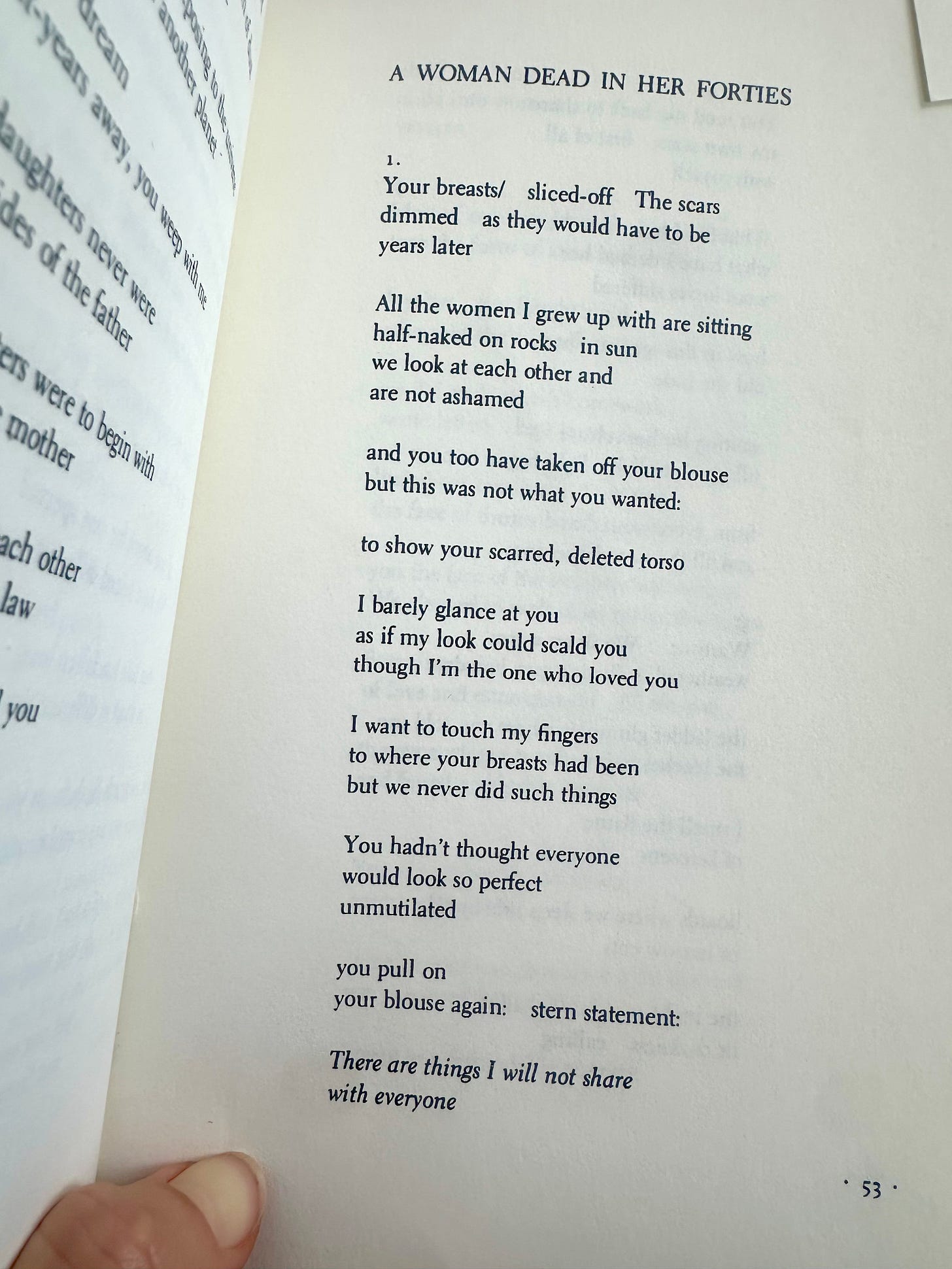

The pages fanned out until my intuition caught the right page and I cracked the book open to see this line first, just minutes after the departure of my masseuse:

(Ps. If you skimmed past that image without reading the entire passage, which is section 1 of 8 from the full piece, I encourage you to scroll back up and read it— It’s worth it.)

I stayed on the first line for what felt like whole minutes, mouth agape, before I even noticed the title of the piece. And that’s when some dread set in.

A WOMAN DEAD IN HER FORTIES

Being 41 at the time (I am now 42), I was wholly disturbed. But I continued on to read the entire poem, which only gets greater and greater, and I wept there on the porcelain throne like God had touched my head. I stood up and shakily walked back into the light, still clutching that sacred paperback and deeply moved —into the realm of wonder, awe, and even fear— by the Mystery.

I was so shocked by the synchronicity of that first line, the world froze. I could not dismiss the astonishing precision of those words, and the timing of my encounter with them… Then and there my inner skeptic sat the fuck down.

Maybe past lives were real, and maybe mine were violent, and my breasts had been sliced off once upon a time… And maybe that is why I was having such a hard time with my surgery experience.

Other women did not seem to have such a hard time. Other women posted on their Instagram stories how all of their energy came back days after the operation. How their immune systems responded with gratitude and their glow returned right away. They raved about how it felt to come home to their natural forms and how they loved their small breasts.

They came back to life so quickly.

My body, on the other hand, only felt more dead.

I felt my age suddenly and heavily, as though a dimmer switch had been gradually turning down on my life force ever since the end of 2023, the year of my 40th birthday. (WOMAN DEAD IN HER FORTIES. I shuddered.)

My body was undeniably upset with me. She hid from my scrutinizing gaze like a scared animal in my new uniform layers of athleisure. Much of what had seemed ‘off’ with my health before - my greatest impetus for going under the knife to begin with - in the end simply felt aggravated by the entire experience. The chronic respiratory infections did seem to improve (praise be!) But my fatigue remained. My anxiety intensified. And the chronic pain in my joints was worse that ever.

Instead of positive changes, what was notably different were the extra pounds I had gained after months of sheltering in my mind, and new numb patches where sensation once been, which constantly signaled “alert: disconnection!” to my subconscious.

But the new addition that bothered me most of all was the new appearance of my breasts; particularly the fresh visible red scars that seemed slightly misplaced at the center of my breasts.

Instead of being seamless, blending into the underside folds like other women’s, my incisions appeared as jarring straight lines, faintly lopsided and clashing with the natural curvature of my breast tissue.

Also, and more disappointingly, one had lifted with the surgery, and one did not, leaving an asymmetry that had never existed before. They now sat on my rib cage like two broken eggs: flat and deflated, nipples like crooked cartoon eyes.

I was no stranger to scars, and these new ones conjured distressing memories for me.

One year prior to getting my breast implants in 2006, I was hit by a car as a pedestrian. I was 21 years old.

I had been at a bar that night with my friends and one of them got in a fender bender as we left. Following behind her in my friend’s Tahoe, we saw the accident and got out to check on her. I was standing on the side of the road when another drive peeled around the corner and slammed into the whole scene where I stood at the center with only seconds to register what was happening.

I remember the realization that flashed in my mind before the collision:

Oh my God. This is how I die.

I felt so cheated. My next flickering thought was how devastated my parents were going to be. Then the car hit my body, smashing me between the two vehicles from the waist down. The pain was incomprehensible. But I was grateful for the lucidity I had to experience it. It meant my brain was safe, and for as long as I could feel the pain, I knew I was alive.

Maybe this moment is where I bonded with pain: when it helped me feel sure I was alive.

It turned out, that was not how I would die. The body is extraordinarily resilient (especially at that age, 21). The recovery was long and hard, though.

To this day, I can hardly believe what I went through… Using my arms to pull my body up and use the bedpan. Living in rehab facility for one month before I went to live in my parents’ living room so I could be taken care of. And the way my mother would walk me to the neighbor’s house to shower because I could not go up and down the stairs.

I recall the story I heard in the hospital about a man who had been hit by a car on the side of the road like me, and lost both of his legs.

I remember the woman I met sitting across from me in the community area of the rehab center, who was paralyzed from the neck down after being shot by her boyfriend.

It could have been worse. I was grateful every day to have the opportunity to heal.

But then (as it does) the gratitude began to fade as I tried to reintegrate into my ordinary life. I was frustrated and embarrassed at age 22 to go back to college classes with a cane. I had a metal rod in my leg then (which I have lived with to this day), and I limped as I was learning to move around on my own again. One knee swelled every day. That pattern of asymmetry remained bothersome.

And the scars were frightful to my eyes. I felt like Frankenstein. It was summer by then so I wrapped and covered them everywhere I went. Even at the beach with my family.

That might sound like some crazy body dysmorphia, which is common for young adults and their egocentric worldviews; imagining that everyone is staring and judging when, in reality, hardly anyone is noticing you at all.

But, in hindsight, I am finding a deep current of grace and compassion for the shock and grief that comes with an irreversible change to the body— in feeling, shape or image.

John O’Donahue calls the face the “icon of intimacy,” alluding to it as a unique and exquisite gateway to the soul, and I have come to recognize the body as an extension of this… A temple of intimacy, perhaps.

Image is meaningful to us. It is the primary gateway to our conscious mind’s intimacy with the soul of this entire unique self, in this unique lifetime. It represents us. And form is how we locate ourselves in the world. All of it is sacred. It matters. It is okay that it matters. And so I have to forgive myself over and over again for my obsession with it, as hard as that may be at times in retrospect.

I had to endure another surgery that year when an error by my surgeon resulted in a crack in the hardware in my femur. In my recovery journey, I had 5 blood transfusions, a fascia transplant, and multiple scar revisions. I lost a lot of weight. My breasts deflated with the fluctuating pounds. I would look at them in the mirror, disturbed by tso many changes in my breasts and body alongside and what appeared me as monstrous leg scars on my shin, knee, and hip.

About one year later, I received a liability payout from the car insurance company for my injuries. I had chosen the path of least confrontation, deciding to take personal injury damages from the drivers’ policy rather than pursuing a complex and uncertain lawsuit for who knows how long and what cost.

I worked at a country & western dancehall at that time, as a beer tub girl, while attending classes at the local university, UTSA. I made great money rolling cold beer bottles in beverage napkins and shivering in the cranked up AC until the club filled with sweaty dancing bodies.

My $500 concert nights at the club were peak wealth for me until that moment. It was hardly an exchange for the suffering (short and long term, it would turn out). I got about $60,000 from the car insurance payout in 2006. I had never had so much money before. I had been through a lot, lost a lot, and finally there I was in the light at the end of tunnel.

Determined to salvage my sex appeal and lost dignity from my scars, I decided to use some of that money to get breast implants. I had never been able to afford it, and the trend was sweeping through my peer group at the time.

I remember coming out of surgery and feeling like my chest was pregnant. There was a soft, quiet, strange hint of seasick guilt, like I had tampered with something that I should not have.

In hindsight, I see that this was the sense of violating the sacred of my body, but I did not have language for it yet. “Intuition” was hardly even a word in my lexicon.

As I adapted to the sensation of having these large water balloons under my pectoral muscles, massaging them to help them “drop”, I also had to adjust to the new life experience of garnering far more attention in public than I had before. It was kind of exciting. And it was simultaneously uncomfortable… Sort of like the feeling of a dream where you find yourself naked in public.

I recall specifically my first time walking through a restaurant in a tank top with no bra on. It was slinky grey and silver, spaghetti strapped. I remember an older woman sitting at a table in the center of the room, casting a side eye of scorn. It wasn’t even pointed judgment… I was struck that it was her natural reaction.

I made a mental note that the days of frolicking around wherever I please without a bra on were numbered. I would be more thoughtful with respect to the crowd.

But I also decided firmly in that moment that I was going to relate to my implants like they were a part of my body. I was going to embrace them, and not allow them (or anyone’s perception of them) to mark me with any sort of shame.

From that point on, I stepped all the way into my new life as the subject of more attention, knowing much of it would be unwanted, whether that was judgement or objectification. It was too late to change my path. There was nothing that could be done to go back. This was my body now. The implants were my breasts now. They were me.

I never looked back…

That is, until 2023 when - upon learning more about what is now called breast implant illness, and I suddenly felt myself beginning to outgrow my old familiar hyper-sexual shape. I decided that the time had come to let them go. So I booked my surgery for January 2024. I was optimistic and ready to rediscover who I might be without them.

But there I was again, about 6 months post-op, facing off with that 18 year-old nagging question: “Why me?”

Every single day since my surgery, I would stop and stare at my scars in the mirror before my shower, covering them with my fingers to imagine what it would be like not to have them, or manipulating my deflated breast tissue around with my hands trying to make my breasts look even again. All the while, I would lament and ruminate… Why didn’t I feel better like the other women? Why didn’t my breasts look pretty like the images I saw at the surgeon’s catalogue of results? Why did mine have to come out uneven? What did I do to deserve for it to be extra hard? Had I made the wrong choice? Whose fault was this?

Most days I felt blame towards my doctor for error in the placement of my incisions. This was my pain story: that he disfigured me. I liked him a lot, but he was supposed to be the best of the best. I felt convinced that he could have - and should have - prevented the asymmetry with more precision.

Then, uncomfortable with my bitterness, I would blame myself for not being more direct and assertive, for not following my gut, and for not asking enough questions when I felt unsure, or being brave enough to speak up when I felt unhappy.

It brought up painful memories of regret, not having stood up for myself more in 2005 after the accident when my doctors made an error in my leg surgery, and just taking the insurance payout instead of standing for myself. I had always wanted peace. I wanted to trust the medical system that saved my life.

And I wanted people to like me so I would be safe. This pattern, as problematic as it has always been, I could grant myself compassion for. Especially if by some wild change, I had been violently harmed in past lives.

I would then seal my daily ritual of discontent by gaslighting myself as overcritical, revoking blame, and wondering if all of my concern was just an echo of that younger dysmorphia…

I would tell myself, “it could be worse,” like so many bad things that had happened in my life, and step into the running water feeling the strange two-sided coin that fate seemed to hand me for this lifetime: cursed and so very blessed all at once.

I deliberated often whether to try to get my breasts “fixed”. But my poor body had been through so much. Sure, it did not feel fair that I had an unfavorable outcome, with one little breast up high and the other low, when they had always been even before. But chasing the illusion of aesthetic perfection by messing with my body was what had brought me to this point of feeling like a patchwork doll in the first place.

Maybe the opportunity in the arising challenge was to see if I could really, truly love myself as I now am.

I would soothe myself by asking, “What would would Joan of Arc do?” Because I knew Joan would not keep fucking around, tinkering with her breast shape. She would get back to her mission.

I sensed the same would have been true for Adrienne, and her mission was poetry. Though she wrote in a different stratosphere of talent, we had that in common.

My mission was poetry too. So every day, I focused on finishing my book, and tried to not to obsess about the loss I felt in my form. I created distance from the fixation that was triggered by the mirror. I left my broken body behind. I would get the book done, and come back to her later to figure out how to “fix” it all.

But there was a monster of grief in the corner behind me every time I passed the mirror, missing the beauty I had not appreciated until it was gone. I dismissed the grief as silly. I was still pretty and still loved, somehow with all of these Bride of Frankenstein secrets under my clothes. And I was alive. The wisdom of waking up in the hospital after the car crash echoed: pain, scars, humiliation, frustration, and setbacks aside, I was alive.

The woman Adrienne Rich wrote about in that poem had actually died of breast cancer, after all. It could have been much worse.

But on that afternoon, the little red book in my hand penetrated my distraction strategy with that common language shared between my masseuse and her words.

The question of “Why is this so hard for me?” had followed me around, just like my grief monster and the synchronicity offered an answer that was broader than “bad luck” or “bad girl” (some sort of great cosmic scolding had certainly crossed my mind when I lamented my star-crossed experiences of fate).

Maybe it was indeed my karma: not punishment for being bad, the way I used to imagine it, but an old soul wound trying to fully heal by coming back to the surface to be seen by me again. A pattern’s invitation for reconciliation.

The synchronicity gave me strange hope for a bigger, more meaningful picture than the frame I had most of the time. The title of the poem bothered me, though. The explant surgery had not exactly worked in terms of the being the “silver bullet” that restored my health and energy.

So then, what would it take to not become a ‘woman dead in her forties’?

What was the message? What might that mean?

That’s what I have been figuring out ever since. I have learned some of the answer to these questions by now, and some of the answers I am still living my way into, as Rilke put it*.

The jury is still out on whether or not my breasts were really chopped off in a past life. But one thing I know for sure us that in order to prevent deadness in my forties, I have to express my feelings. I have to share my stories. I have to honor the grief, the anger, and the Grace that has been bottled up by silence, so it can flow freely through my veins and bring me back to life through connection.

I have been hesitant to share my experience publicly, because it is true, as Adrienne Rich says in that final line of that page, “There are things I will not share with everyone.”

Part of my healing journey is me walking this tight rope: holding and protecting my sacred secrets, while returning to the collective conversation with stories that are vulnerable enough to penetrate and touch other hearts.

Just like my implants, I can’t control what people will think of my stories, but they are mine. They are a vital part of me. And sharing them is a way of reclaiming myself.

I think that this kind of reclaiming might be the most healing thing we can do for ourselves: the surest way to begin to come home.

A Note from Caitlyn:

This post is the first entry in what will be a series, recounting my healing journey after removing my breast implants. I hope my lessons and insights can help all readers find more compassion for the challenges that often come with body modifications, and can support you all in making clear choices for you while potentially forgoing some of the harder lessons.

I am not sure how many parts will come through this red thread. At least one more. I hope if you enjoyed this post, that you will follow along with me for the next, where I will share more of what I have learned in the interim.

And if you are reading this as someone who is curious about breast explant surgery and want to ask a question, please drop it in the comments. I will do my best to weave my responses into the next post “coming home to the body I left behind, part 2.”

Thank you so much for reading with me today. It means more than you know.

*Footnote— Rainer Maria Rilke, on unresolved questions:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

If you enjoyed this, please share where it feels right for you. And if you want to stay connected, check out www.poetqueen.com to learn more about me and what I am offering in my work with ritual arts, creative expression, and emotional alchemy.

This has moved me deeply; as someone without any shared context (implants, explants etc.), but as someone who lives in a body that has lived through much of its own. Thank you for sharing of yourself so purely and completely, Caitlyn.

I think it’s a harder story to tell, when things don’t go “well” or as expected, but it’s comforting for people like me who also don’t come out of explant unscathed. Thanks for sharing your story 🙏